Download the Prostate Cancer Centre's printable PDF booklets to read offline.

Prostate Cancer - General information

Prostate Cancer - Brachytherapy

Prostate Cancer - Radical Prostatectomy

Prostate Cancer - External Beam Radiotherapy

Use the Prostate Cancer Centre's treatment selector to get an idea of what treatment is right for you.

Select this link to view the treatment selector

©The Prostate Cancer Centre UK Ltd 2005. All rights reserved.

| What is Prostate Cancer ? |

The Prostate Cancer Centre provides a single point of referral to specialists at the forefront of the treatment of localised prostate cancer.

Normally in the prostate, as in the rest of the body, there is a continuous turnover of cells, with new cells replacing old dying ones. In a cancer the balance between the new and old cells is lost, with many more new ones being made and older ones living longer.

Cancer of the prostate can be defined as uncontrolled prostate cell growth.

The malignant growths are known as tumors. They differ from benign tissue enlargements in that the cancerous cells can spread (metastasis) to to surrounding tissue, including the rectum and bladder.

However, sometimes the cancer can be detected before it has spread outside the prostate. At this stage the cancer is still treatable with a good rate of success.

Cancer cells can spread directly to neighbouring parts of the body, such as the seminal vesicles or bladder, by growing outwards through the outer wall or capsule of the prostate. They may occasionally spread through the blood stream and implant in growing bones of the spine.

Finally, cells can also be spread through lymph vessels. These vessels are like a second system of veins except that, instead of blood, they contain a milky fluid that is made up of the cells waste products. Lymph vessels drain via lymph nodes (special bean shaped filters) that eventually empty back in to the blood circulation. During this process the lymph nodes can also be invaded by cancerous cells.

Prostate cancer is now the most common cancer in men in the UK with nearly 20,000 men being diagnosed with the disease and 10,000 men dying from it each year. However there have been many recent advances in detecting and treating prostate cancer and patients who are diagnosed early can now have a high chance of cure.

Prostate cancer rarely occurs before 50 years of age and is most commonly seen in men in their 60s and 70s. Indeed, it seems almost inevitable that if one lives long enough, prostate cancer will develop. However, this does not mean that all men will be aware of the cancer, need any treatment or even die because of the disease.

The full answer to this question is not known.

Nevertheless, there are a number of factors that can increase the chance of developing prostate cancer. Relatives of patients with prostate cancer have an increased risk of developing the disease themselves, especially if their father or brother were affected.

The disease is more common in the Afro-American population and rarer in the Chinese. There also appears to be a link with people living in urban areas exposed to pollution and to those consuming large quantities of dietary fat.

Diet and prostate cancer

Studies in twins suggest that 45% of prostate cancers are caused by genetics. Migration studies have confirmed the strong influence (55% of prostate cancers) of environmental factors on the risk of developing prostate cancer.

An individual's genetic make-up cannot be altered but environmental influences, the most important of which are dietary, can be modified to reduce this risk.

The following have been shown in medical studies to:

Reduce the risk of prostate cancer

- Vitamins A, D & E

- Selenium - found in Brazil nuts

- Carotenoids - especially lycopene, found in (particularly cooked) tomatoes.

- Phytoestrogens - especially soy products, as well as cereals, fruit and vegetables

- Chinese green tea

Increase the risk of prostate cancer

- A diet which is heavy in animal fat

- Obesity

There are often no symptoms associated with the early stage prostate cancer. As the disease progresses and the tumour enlarges it may compress and constrict the urethra which runs through the gland, obstructing the flow of urine during urination.

In this situation the patient may notice a weak, interrupted stream of urine that requires straining to urinate. On completion he may still feel that the bladder is not empty.

However these symptoms are not specific to prostate cancer and are most commonly found in benign non-cancerous enlargements of the gland.

Blood in the semen may also be a sign of prostate cancer, although again it is a common finding and not normally related to malignancy.

If a tumour has spread to the bones then it may cause pain. The spine is the most common site for this to occur.

During a consultation the doctor will initially ask the patient questions to ascertain their general medical health and to see if they are experiencing any symptoms associated with prostate cancer (although, as has been mentioned, such symptoms are not specific to prostate cancer).

Physical examination

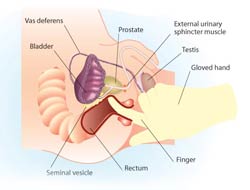

Having made a general examination the doctor will then need to perform a rectal examination to feel the gland. A gloved lubricated finger is inserted in to the back passage (rectum) to assess the size and shape of the prostate gland.

Blood test

The prostate can be evaluated be testing for the level of a particular protein in the blood called PSA (prostate specific antigen). Prostate enlargement tends to cause an increase in the level of PSA, with malignant tumours producing a greater increase than benign enlargements. Other, unrelated, conditions can also cause PSA to rise, such as a urinary infection.

The normal range in general for PSA is between 0 and 4 nanograms per millilitre (ng/ml) and as this level rises the chance of a patient having prostate cancer also increases. Clinicians often use an age related PSA range as shown below. The PSA gradually rises with age due to an natural increase in benign prostate tissue, that also makes PSA, which occurs with aging Patients with widespread cancer may have levels of more than 100 nanograms per mil.

Age related PSA levels

| Age PSA ng/ml | ||

| 50-59 years | 60-69 years | 70+years |

| 3 | 4 | 5 |

It is important to bear in mind that PSA is prostate specific but not prostate cancer specific. Although a slight elevation in PSA may indicate an underlying prostate cancer it is by no means definite.

Ultrasound examination and biopsy

The prostate can be visualised with ultrasound; a device often used to scan pregnant women. To visualise the prostate a well lubricated probe, similar in size to a finger, is inserted in to the rectum and images of the prostate are displayed on a screen. This technique also provides pictures of the seminal vesicles and tissues surrounding the gland.

The images are produced to help identify areas within the gland that may be malignant, but the only way to prove that there is a cancer present is to take a biopsy (a small piece of tissue obtained by a special needle).

If a biopsy is to be performed at the time of the ultrasound scan the patient will be forewarned. A small needle is inserted along side the ultrasound probe, which can then be moved in to the area of the gland in question.

The procedure is no more painful than giving blood due to the use of local anaesthetic. The doctor will give the patient an antibiotic to help prevent any infection occurring.

Typically ten biopsies are normally taken which are then analysed in the laboratory and the diagnosis confirmed. After the procedure, it is quite common for the patient to see some blood in his urine, semen and stools. This usually settles over a week or two.

Bone scan

Once a diagnosis of prostate cancer has been made, and if spread is suspected (usually by the level of the PSA), a bone scan can be used to see whether the tumour has invaded bone.

For this painless test a tiny, harmless quantity of a radioactive agent is injected in to a vein. This makes its way to any cancerous deposits within the skeleton and sticks to them. After a few hours the patient is scanned by a special camera, similar to an X-ray machine, which detects these deposits, if present.

Other tests

Two other types of scans are available. A computer tomography (CT scan) or magnetic resonance imagining (MRI) scan is sometimes used to obtain detailed pictures of the prostate and the surrounding tissue.

Both are quite painless. The CT scan utilises X-rays and the MRI uses magnetic fields to produce their images.

What does the stage of prostate cancer mean?

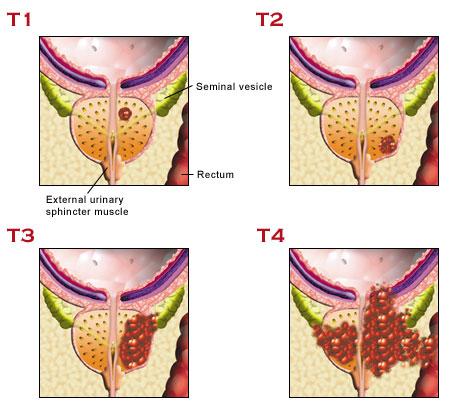

The stage of a prostate cancer refers to how far the cancer has spread.The classification commonly used to stage prostate cancer in the UK is shown here in a simplified form. (The prefix T is used by convention to identify the tumour stage, i.e.T1 or T2). It is very important to remember that although all prostate cancers have the potential to progress, it may take many years to pass from Stage 1 to 4.

Stage 1

Earliest stage, where the cancer is so small that it cannot be felt on rectal examination, but is discovered in a prostate biopsy or in prostate tissue that has been surgically removed to ‘unblock’ the flow of urine (as in a transurethral resection of the prostate – TURP).

Stage 2

The tumour can now be felt on rectal examination, but is still confined to the prostate gland and has not spread.

Stage 3

The tumour has spread outside the gland and may have invaded the seminal vesicles.

Stage 4

The tumour has spread to involve surrounding tissues such as the rectum, bladder or muscles of the pelvis.

What does the grade of a prostate cancer mean?

The grade of a cancer is the term used to describe how aggressive the disease is and whether it will progress quickly (months) or slowly (years). The grading assessment is made by a Pathologist in the laboratory, looking at the prostatic cells under the microscope. The grading system used for prostate cancer is known as the Gleason Scoring system, named after the Pathologist Donald Gleason, and ranges from 2-10.

The Pathologist will identify several of the prostate cancer cells in the biopsy. Having identified the largest and second largest areas of cancerous cells, he or she will assign each area a number known as the Gleason grades. These grades range from 1-5, with grades 1-3 tumours least likely to spread and grades 4 and 5 most likely.

The Gleason Score is calculated by adding the two Gleason grade numbers together – thus, the score ranges from 1+1=2 to 5+5=10. Therefore, a Gleason Score of 3+2=5 suggests that most of the cancer is Gleason grade 3, with a smaller amount of Gleason grade 2. Prostate cancers with a Gleason Score of 7 or greater will always contain at least some Grade 4 tumour and hence have a worse prognosis. Understanding of the pathological grading is of great importance for both the clinician and the patient, as it will determine which treatment options are available, as well as their likely success. Many regional cancer centres will arrange for a specialist Pathologist to review the microscopic slides of a patient’s prostate cancer cells to confirm the diagnosis before treatment begins.

| Gleason Scale - Microscopic appearance of prostate tissue | ||

|

||

| Least aggressive Grade 1 (Gleason score 2-4) |

Moderately aggressive Grade 2 (Gleason score 5-7) |

Most aggressive Grade 3 (Gleason score 8-10) |

Understanding what prostate cancer is and being aware of the medical terms used by consultants and surgeons can start to make your diagnosis easier to cope with. From here we would suggest visiting the treatments section to find out what can be done to help tackle prostate cancer.